[6-minute read]

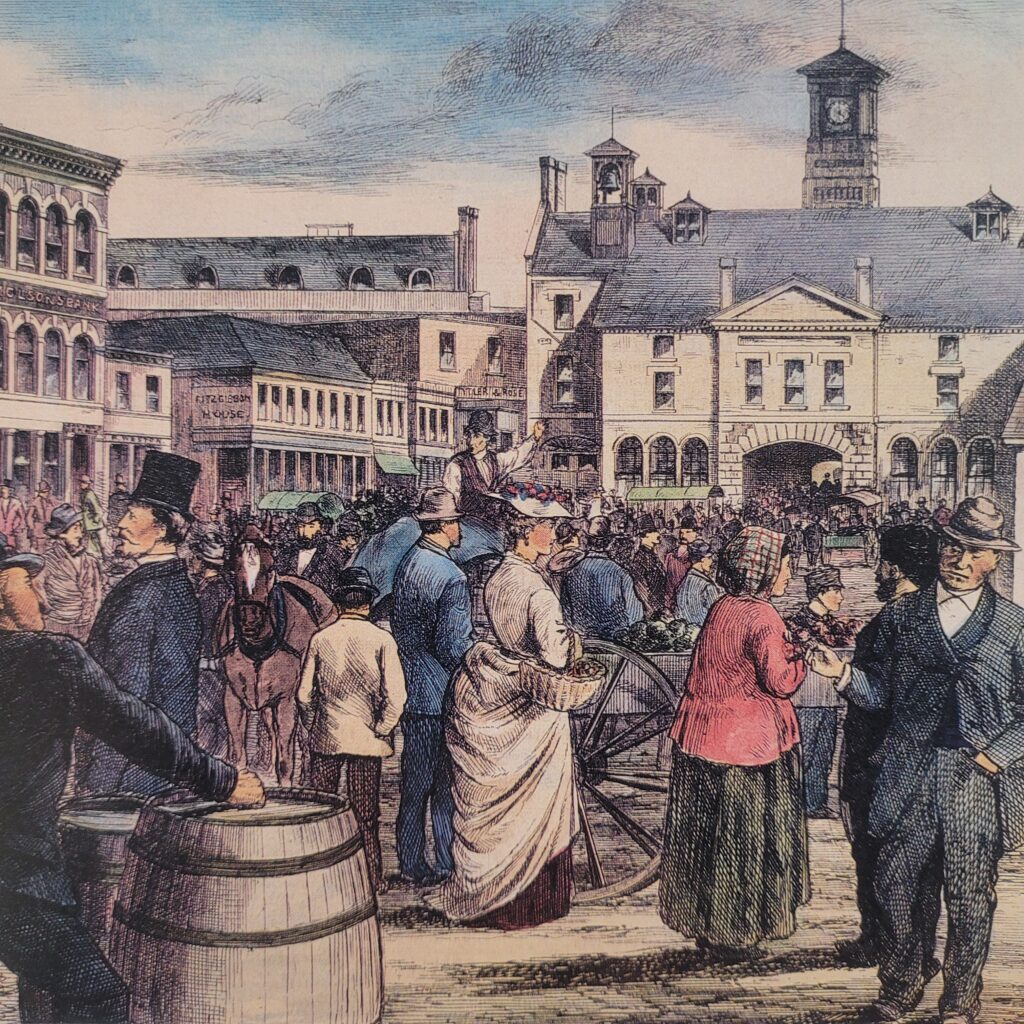

Picture yourself in London in the 1870s.

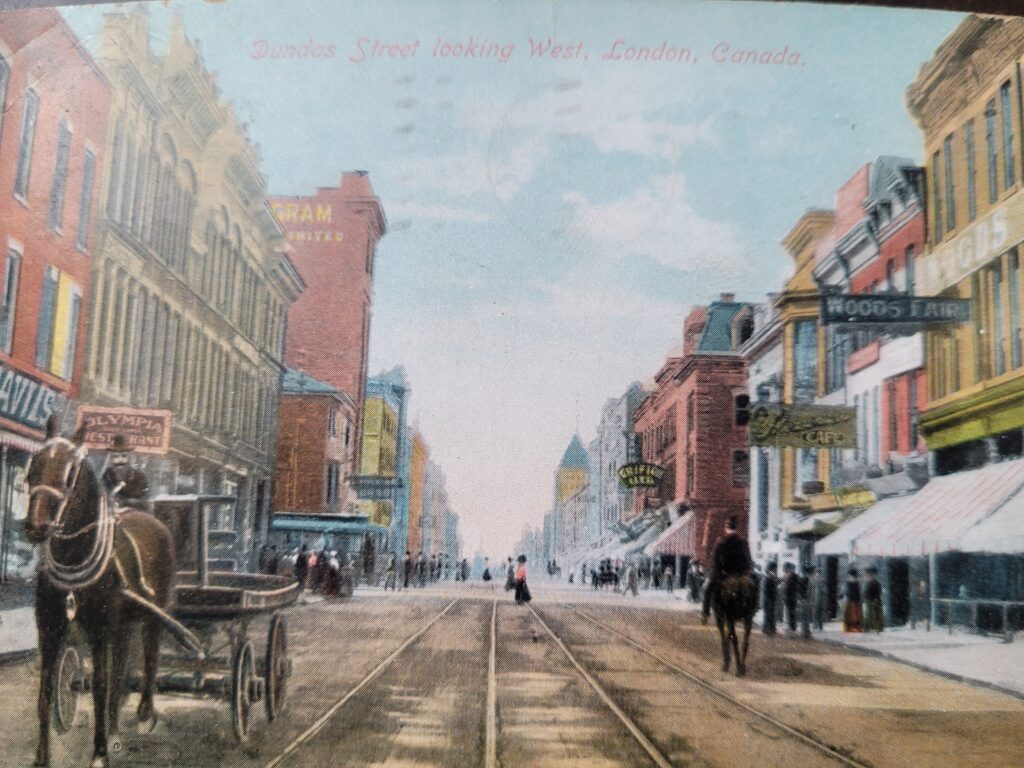

The streets were bustling, industry was growing, and the city had established itself as a proud hub in Southwestern Ontario.

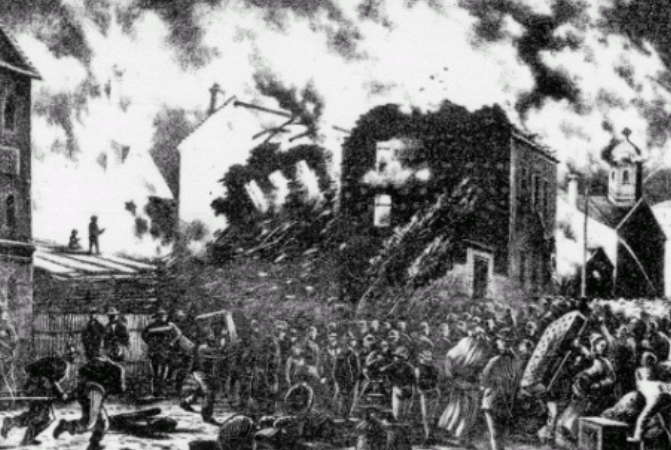

(Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Canadian Illustrated News, 1875-11-13, vol.XII, no. 20. 305)

But this promising city had a big problem, one that kept its citizens and council members awake at night.

The Constant Threat of Fire (1852 – 1875)

In an age where a single spark from a lantern or a stove could spell disaster, London had no reliable water supply to fight fires. And they had no fire hydrants!

Between 1852 and 1875, London experienced 484 fires, leading to a financial loss of over $1,000,000. Although many of the fires were minor, there was typically one major fire every single year in and around the downtown area.

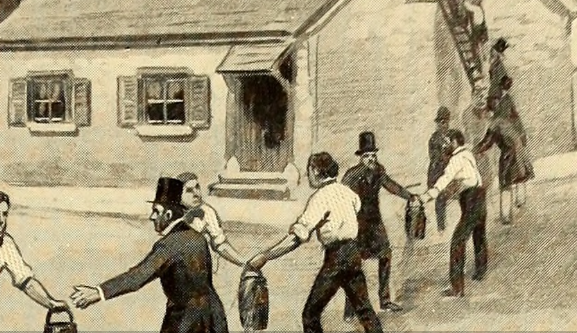

When a blaze started, bucket brigades were often the only defence. It was a heartbreakingly futile effort against a roaring inferno.

(Photo credit: Wiktionary)

Time and again, valuable buildings, businesses, and homes were burnt to the ground.

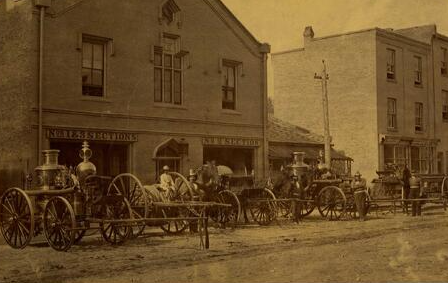

Even the new pumper wagons manned by professional firefighters were largely useless without the ability to generate enough water pressure and without a plentiful water source to draw from.

(Photo credit: Western Archives and Special Collections, AFC49-S1-I60009)

This was more than an inconvenience; it was an existential crisis. As other Ontario cities like Toronto and Hamilton modernized their infrastructure with pressurized waterworks, London’s City Council grew increasingly concerned.

How could they attract new businesses and industries to London if they couldn’t guarantee the most basic municipal service – safety from fire?

A Modern Solution for a Growing City (1875)

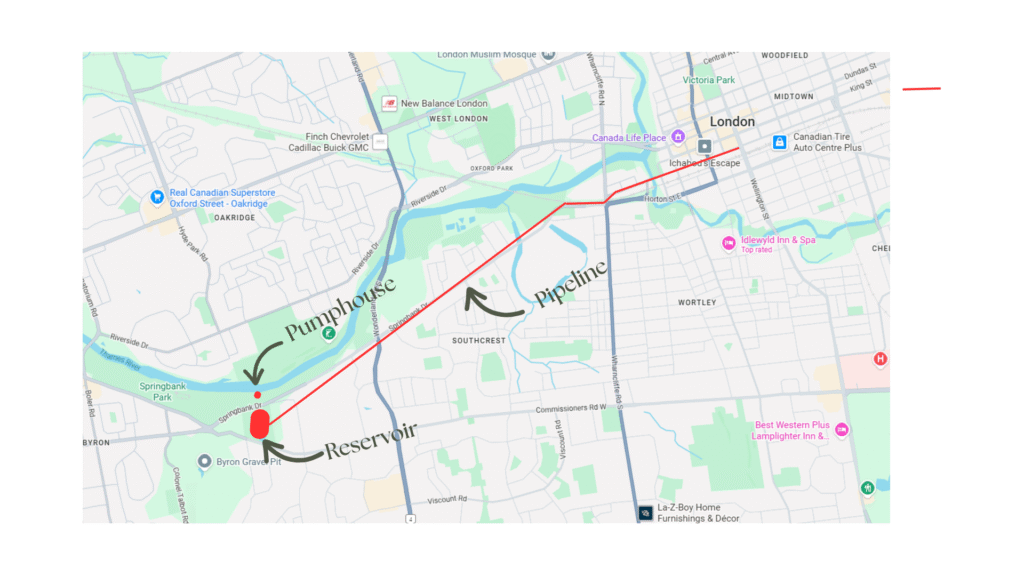

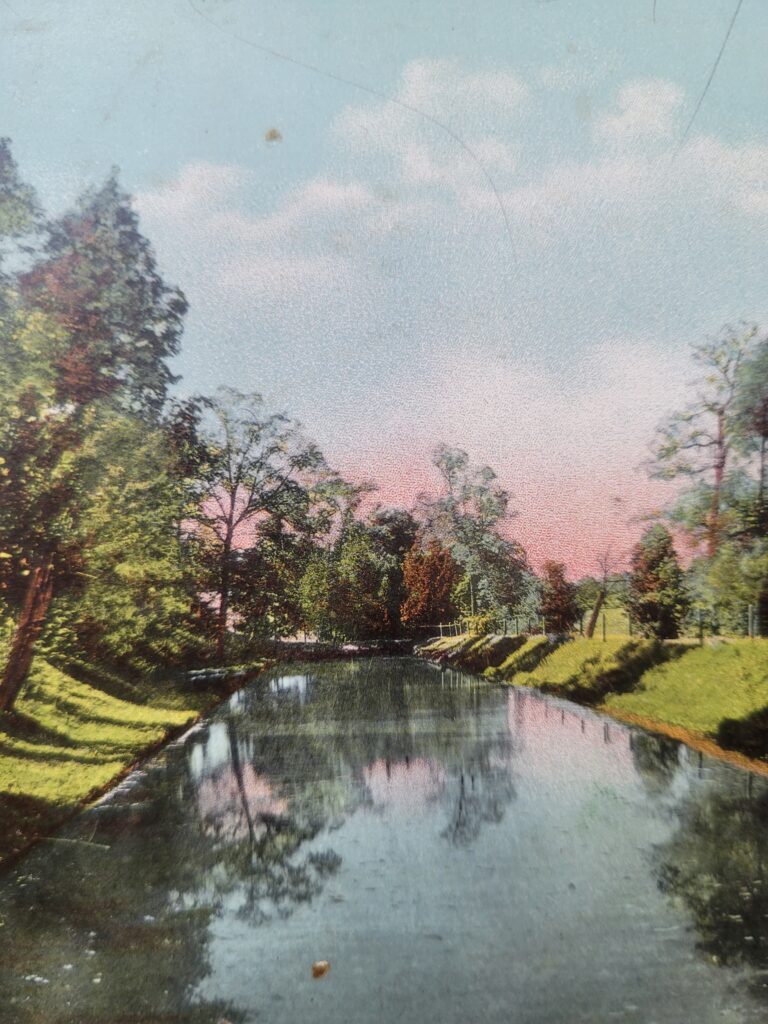

The solution was clear: build a waterworks. The plan they came up with was a marvel of 19th-century engineering. They chose a site to the west of London where six natural springs flowed from the side of a big hill.

Their vision was to pump the clean, spring water up to the top of the 83-metre-high hill where a massive reservoir would be built. From there, gravity would do the rest, sending water through a six-kilometer pipeline to London to feed the fire hydrants soon to be positioned at nearly every street corner in the city.

(Made with Google Maps)

The Great Debate: A Dream Delayed, But Not Denied (1875-1877)

It seemed like the perfect plan. But there was one major hurdle: the estimated $400,000 price tag.

For two years, from 1875 to 1877, the waterworks became a hotly debated topic.

City Council, understanding the critical need, put the issue to a public vote. Not once, not twice, but three times.

You can imagine the debates, the fear of rising taxes clashing with the vision for a secure, modern city.

Meanwhile, London continued to burn. For example, in the four months following the first vote, there were 34 fires.

Finally, perseverance paid off. On the third try, Londoners voted “yes” on December 14, 1877.

Shortly thereafter, a loan for the project was secured, with the promise that shovels would hit the ground in 1878.

The Legacy of a Watershed Moment (1879)

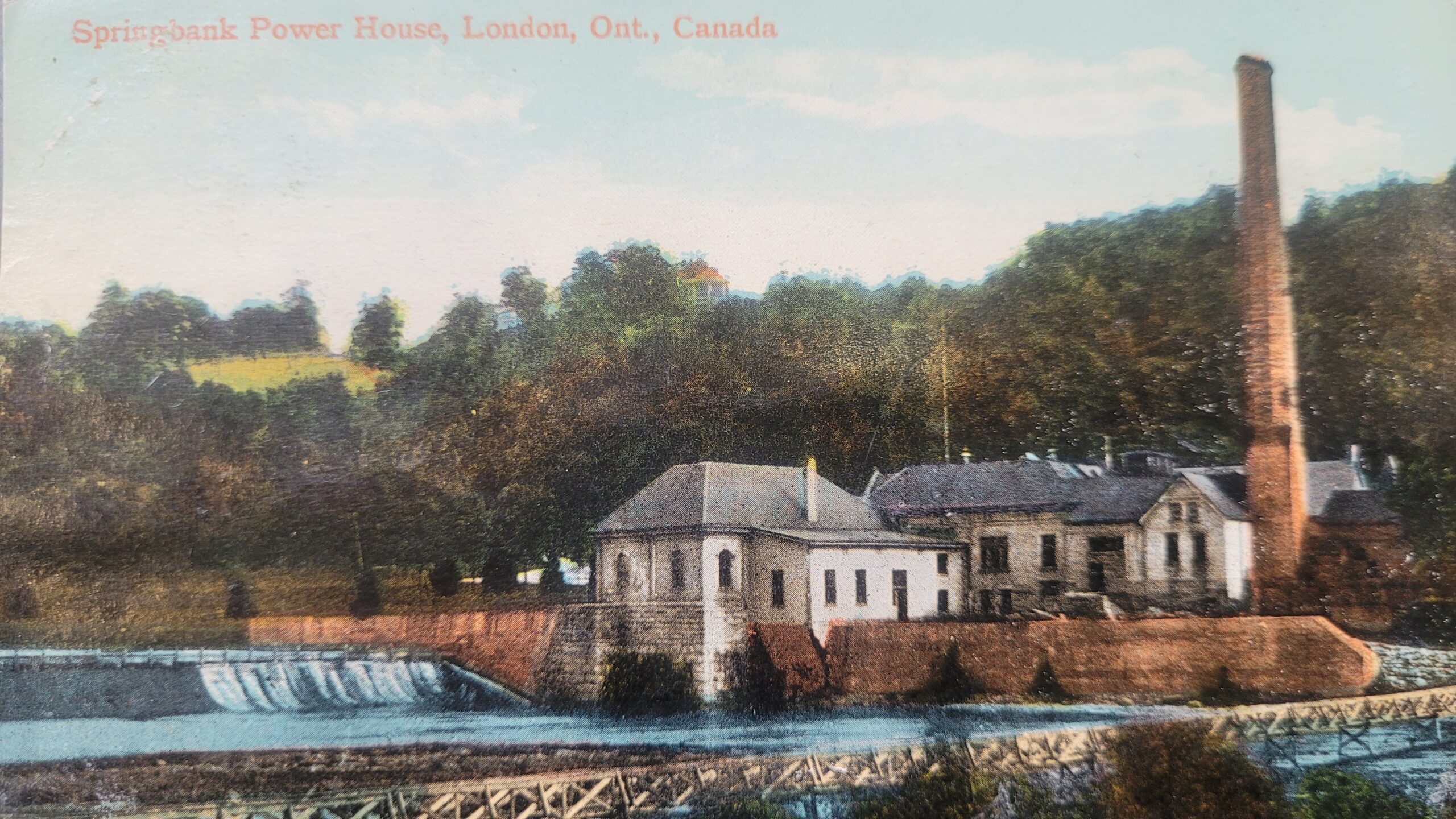

The completion of the Springbank Waterworks in January 1879 was a transformative moment for London.

It wasn’t just about the installation of those first, life-saving fire hydrants. It was about confidence. It was a signal to the world that London was open for business, ready to grow, and committed to the safety and prosperity of its citizens. The city could finally breathe a sigh of relief, no longer living in the shadow of the next great fire.

(Photo credit: London Post Card Album #2, Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library, London, Ontario, Canada)

(Photo credit: London Post Card Album #2, Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library, London, Ontario, Canada)

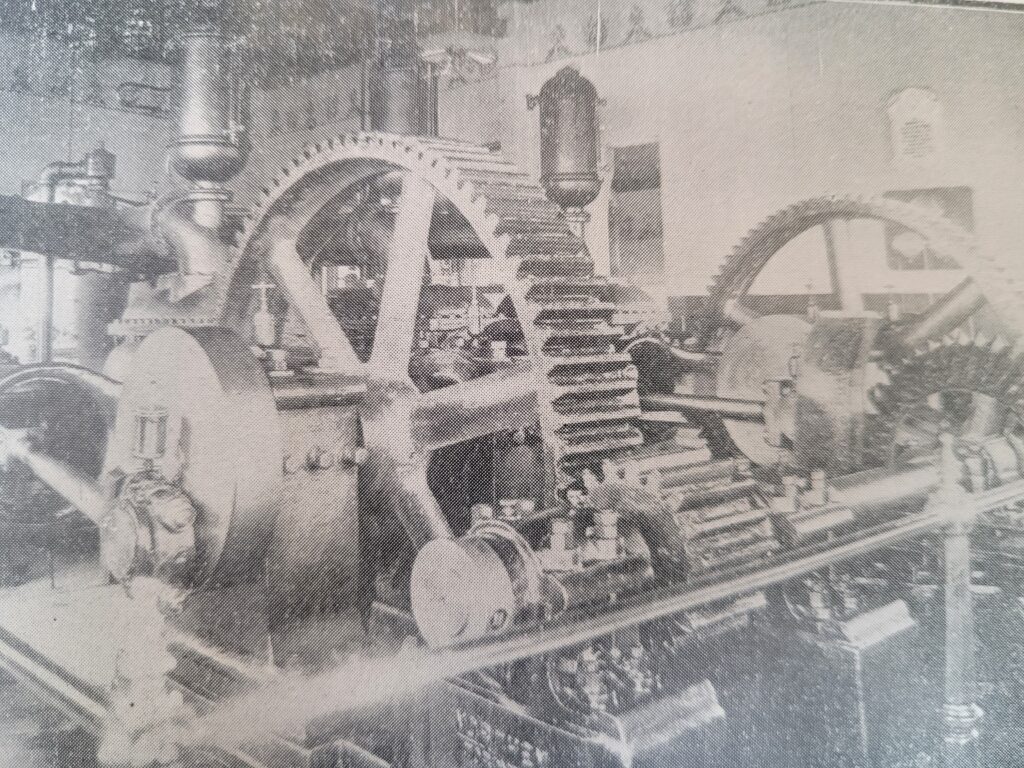

(Photo credit: Public Utilities Commission 27th Annual Report to the City of London, 1905)

(Photo credit: The Live Wire, July 1920)

In 1879, there were 180 fire hydrants in the city of London.

And today?

The latest figures from July 2019 show that, after 140 years of city expansion, the number of fire hydrants in London had grown to 7,614.

Discovering the Layers of Our City (Today)

This story is just one of the multifaceted aspects that make London such a fascinating place to explore.

The legacy of the 1877 waterworks decision is all around us: from the historic buildings in the downtown core that are still standing today because of the improved fire protection, to the continued beauty of Springbank Park, where it all began.

(Photo credit: London Post Card Album #2, Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library, London, Ontario, Canada)

(Photo credit: Lawrence Durham)

(Photo credit: Lawrence Durham)

History isn’t just in our museums; it’s written into the very fabric of our city, waiting for curious minds to discover.

(Photo credit: Lawrence Durham)

Hi, I’m Lawrence – bicycle tour guide, teller of tales, and a huge fan of our city’s unique history. I love sharing hidden stories like this one that help you discover the best parts of London.

If you’d like to see where these events occurred, why not join me on a guided bicycle tour?

Leave a Reply