[5-minute read]

The Thames River, London’s liquid spine, may be a scenic backdrop for cyclists and kayakers today, but it does have a darker past.

For decades, we treated the Thames like a bottomless pit. Imagine a time when every toilet flush, every factory’s chemical byproduct, and every oily trickle from the street headed straight for the river. There was no “treatment.” There was only conveyance.

The river, once teeming with fish, became an open sewer. It was so polluted that by the mid-20th century, calling it “water” was generous; it was more of a biological hazard with a current.

The wake-up call was as pungent as you’d expect. The stench in summer was unbearable. The river was dying, and it was our fault. This environmental embarrassment sparked a revolution in thinking. We realized a fundamental truth: you cannot continue to use your river as a garbage dump and still somehow expect it to remain a resource.

The Great Separation: Where Things Started to Flow Correctly

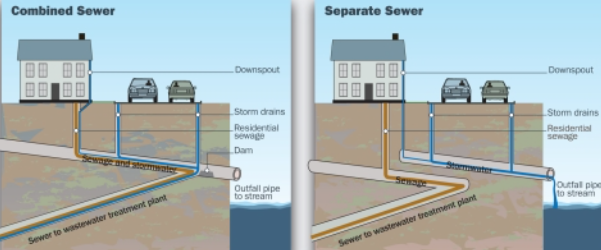

The single most important fix was the separation of the sewage system from the stormwater system. We stopped piping our raw wastewater directly into the river. Instead, wastewater got sent to a treatment plant, while rainwater was managed separately.

(Illustration Credit: EPH Publishing)

But that was just the first step.

Stormwater Management Ponds

We quickly learned that even rainwater running off streets and parking lots carries a nasty cocktail of oil, heavy metals, and debris. Sending that straight to the Thames was only marginally better than sending sewage into the river. So, London got smart. It started building stormwater management ponds.

(Photo credit: Lawrence Durham)

These aren’t just decorative puddles. They’re the river’s kidney dialysis units. When rain falls, instead of gushing untreated into the Thames, it’s channeled into these ponds. The ponds slow the flow, allowing sediment and pollutants to settle out before the cleaner water is gradually released into the river. It’s a simple, brilliant mimicry of nature’s own filtering process.

Step 3: Cleaner water leaves the stormwater pond and flows into the watercourse.

(Illustration Credit: City of Hamilton)

But it’s only when you add rain gardens and permeable pavement that let water soak into the ground like a sponge instead of racing across concrete that you finally have a city learning to work with the water cycle, not against it.

The Downstream Domino Effect: It’s Not Just Our Problem

Here’s the kicker: a river doesn’t care about city limits. The problems we create in London don’t stay in London.

(Source: London Environmental Network)

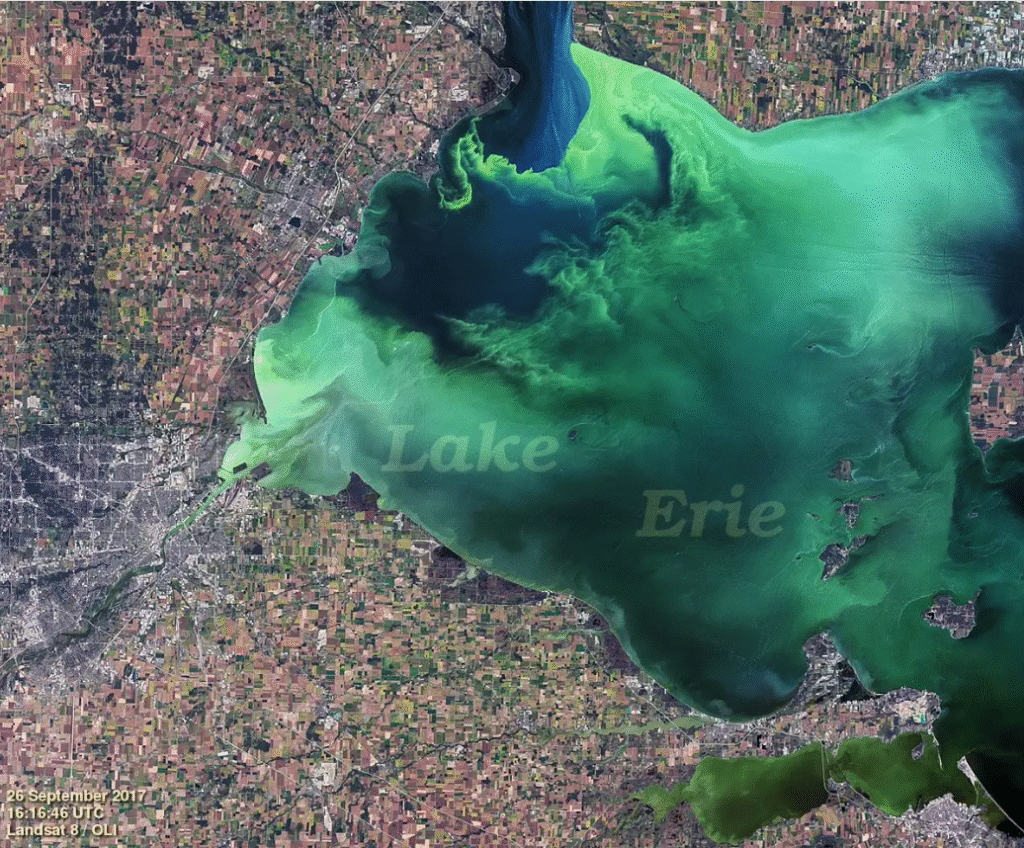

When fertilizers from lawns in London, along with manure from farms along the river, packed with phosphorus and nitrogen, flow downstream, they feed massive algae blooms in Lake Erie. These blooms can create dead zones, suffocating aquatic life.

(Photo credit: NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory)

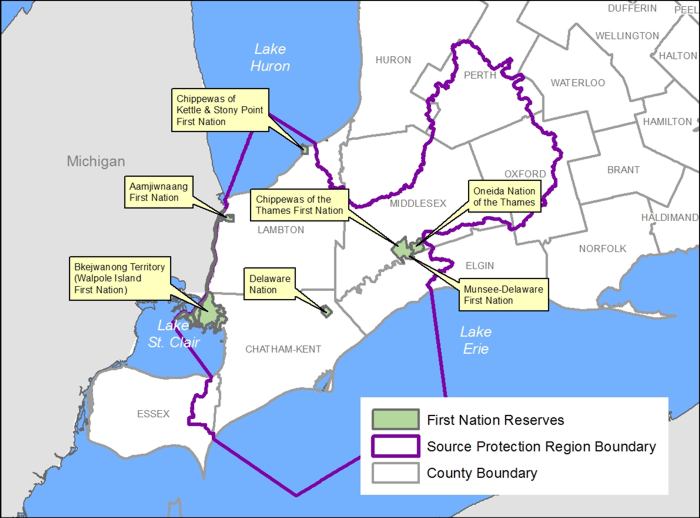

The health of our river is not a local vanity project; it’s a regional responsibility. Every stormwater management pond is a small act of apology and repair—a commitment to sending cleaner water to our downstream neighbours, including the Indigenous communities on the lower Thames River, who have lived alongside and depended on the river for millennia.

(Illustration Credit: Upper Thames River Conservation Authority)

The Thames River today

The Thames River today is a testament to what happens when a city decides to clean up its act. The fish are returning. The smell is gone. While you still shouldn’t drink from it, the river is on a remarkable journey back to health. Those unassuming stormwater management ponds dotting the city are the unsung heroes in this story, quietly filtering our mistakes and giving the Thames a fighting chance.

It’s a powerful lesson: even the most damaged relationships can be healed with a little effort… and a lot of filtration.

(Photo credit: Lawrence Durham)

(Photo credit: Lawrence Durham)

Hi. I’m Lawrence – bicycle tour guide, storyteller, and lover of puns.

Reading about the Thames River comeback is one thing, but pedaling along its revitalized banks and seeing those stormwater management ponds in action is quite another. If you want to experience London’s environmental story, come explore with me. I help curious folks like you discover the best parts of London, from a bicycle seat, of course.

Leave a Reply