[5-minute read]

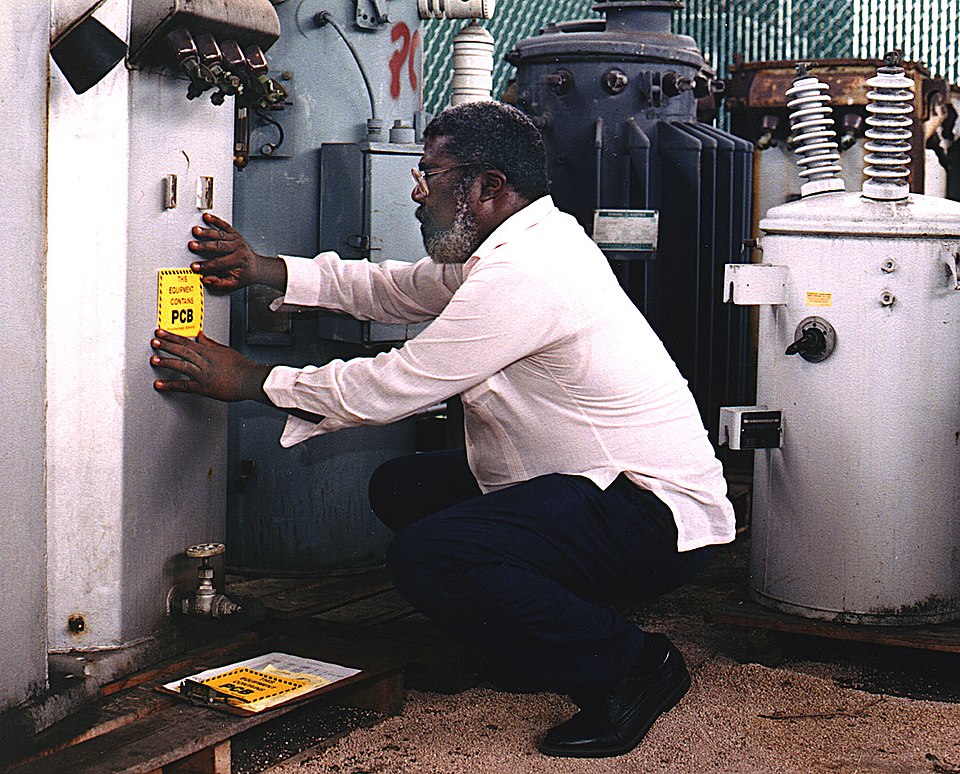

PCBs (or Polychlorinated Biphenyls) were once viewed as a “miracle” substance. That’s because PCBs are non-flammable, chemically stable, and excellent insulators.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, the Westinghouse plant on Clarke Road in London manufactured essential electrical components like transformers and capacitors.

And the key to their success was PCBs.

(Photo credit: London Free Press, Collection of Photographic Negatives)

The Hidden Danger: Understanding the PCB Threat

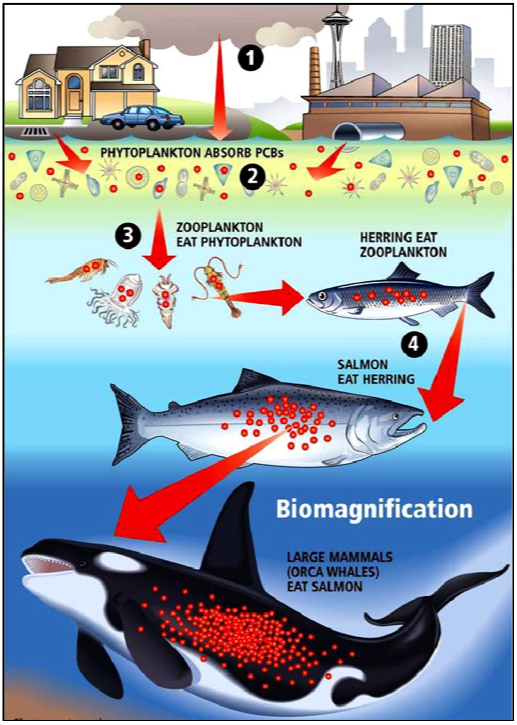

In the early 70s, studies revealed the risks of using PCBs:

- They are highly toxic and carcinogenic chemical compounds.

- They bioaccumulate, traveling up the food chain, becoming more concentrated in animals (and humans) at the top.

- They persist and can remain in the environment for decades.

(Source: Enviroforensics)

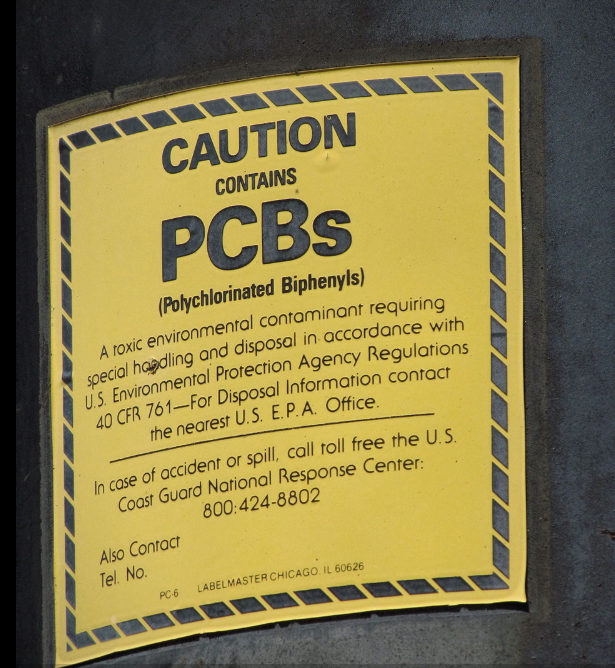

By the late 1970s, production of PCBs was banned across North America.

(Photo credit: Sturmovik)

(Photo credit: Sturmovik)

(Photo credit: US Army Corps of Engineers)

Even though environmental agencies across North America enforced the 1970s ban, PCBs continue to pose health problems today due to their lingering presence in soil and sediment, and from products that were made before the ban.

Now back to Westinghouse

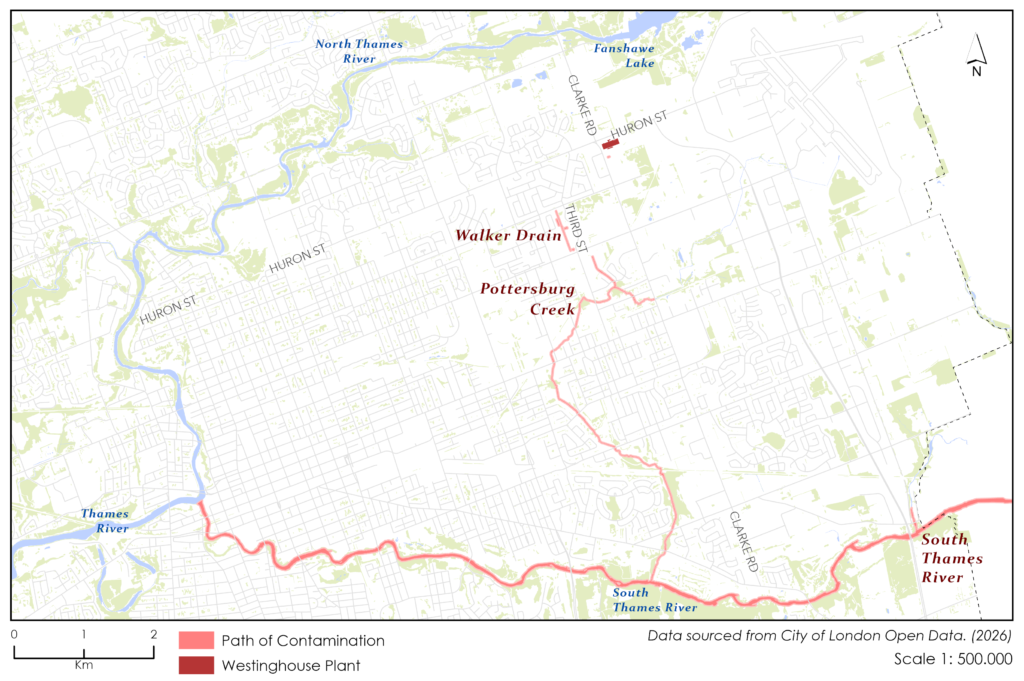

Like many sites across the continent, Westinghouse initially disposed of its PCB-laden materials (either knowingly or unknowingly) on the ground around its property.

Then PCBs from the contaminated soil leaked into the nearby Walker Drain and Pottersburg Creek, especially after heavy rains. From there, the PCBs found their way into the south branch of the Thames River.

(Photo credit: Bishnu Sarangi)

(Map by Nathalia Celeita)

How The Government Fixed the Problem (Temporarily)

In 1984, the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) ordered Westinghouse to create a closed, controlled, secure containment facility to contain PCB-contaminated material from their property.

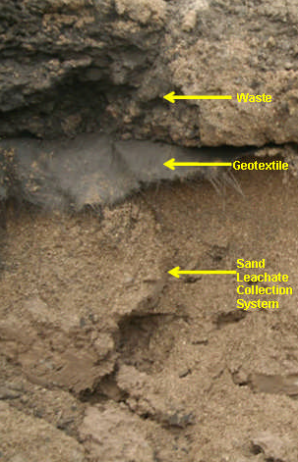

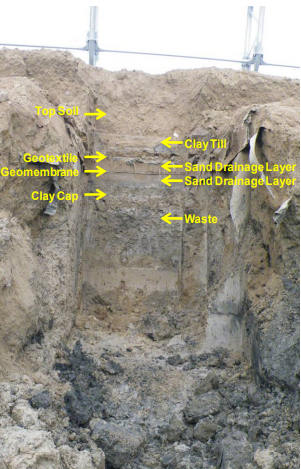

The facility consisted of four containment cells lined with a non-permeable synthetic liner and about 24 inches of clay. The lined cells were surrounded by a sand/gravel leak detection zone contained within a secondary seal of clay.

The ministry monitored the site monthly, and thankfully, no leaks occurred.

(Photo credit: Geo2010)

In 1985, the MOE purchased the containment site to store MORE PCB-contaminated soil originating from OTHER industrial properties, as well as sediments cleaned up from Pottersburg Creek and Walker Drain.

And that’s how London came to have the LARGEST STOCKPILE OF TOXIC PCBs IN CANADA.

The Permanent Solution 24 Years Later (Excavation, Destruction, and Restoration)

In the 1980s, no technology or approved sites existed for the safe destruction of PCBs.

Secure storage was the only option available.

However, by the late 2000s, that all changed as cost-effective and safe methods for permanently destroying PCBs were developed.

Decommissioning of the Clarke Road site began in February 2009, and the first truckload of waste left the site in June. Numerous safety measures were in place to protect community health and safety throughout the project. Those precautions were backed up by constant monitoring of local air, dust, surface water, and groundwater.

(Photo credit: QM Environmental)

More than 104,000 tonnes of PCB-contaminated waste stored in vaults were safely removed from the site by Dec 14, 2009. In all, over 2,800 truckloads went to a licensed facility in Quebec for destruction.

With the treated material gone, the site was backfilled with clean soil and re-vegetated for potential future use.

Total cost: $100 million.

A New Chapter: What This Cleanup Means for London

This story is more than an industrial report—it’s a narrative of renewal. It reveals a city that confronts its history with honesty and science, investing in a healthier future for its land and people.

The cleanup is an example of turning a challenge into a point of pride, demonstrating that environmental responsibility and community well-being are central to our identity.

(Photo credit: Ben Durham)

Hi. I’m Lawrence, bicycle tour guide, storyteller, and lover of the environment.

This PCB story is just one example of the many unique things I’ve discovered while riding my bicycle around London.

It’s my personal mission to help curious folks like you discover all parts of London… from the pleasant to the not-so pleasant, all from the seat of my bicycle, of course. If you want to experience a city that’s actively shaping a brighter future for everyone, I invite you to come on a bicycle tour with me.

Leave a Reply